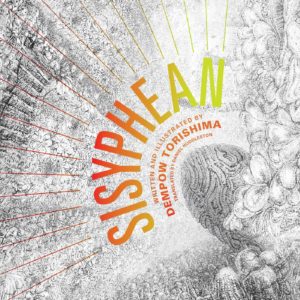

Of Meatpleats and Screwbones—Dempow Torishima’s SISYPHEAN

Of Meatpleats and Screwbones—Dempow Torishima’s SISYPHEAN

Cronenberg meets Kafka meets Ligotti meets H. R. Giger in Dempow Torishima’s “Sisyphean”, a Japanese New Weird novel that is now available in English translation and imagines a future of biotechnology and genetic manipulation, which is built from meat, skin, and bodily fluids.

Haikasoru aims to make selected Japanese literature available for an English-speaking audience—and the newest contribution to this is “Sisyphean” (Kaikin no to) by Dempow Torishima. The novel has approximately 300 pages and was originally published in Japan in 2011. Since March 2018, it has been available in print and as eBook in the English translation by Daniel Huddleston.

It is difficult to do justice to the unique, exquisite strangeness of the novel and its universe in a review, because the novel is a venture into unexplored regions, an incredibly dense and complex experiment in language and content that is without equal in the literature I know. In just 300 pages, Torishima unfolds a universe (with wonderful illustrations by himself) of space travel and bio-horror, Japanese mythology and nightmarish work cycles, genetic manipulation and a search for meaning that requires a lot of time to read and even more to understand.

The novel narrates in four parts the stories of a worker in an organic factory, a young taxonomist in a world of mutants, an invisible “dodgejobber”, and a caravan of yeti-like creatures, that each illustrate another facet of the universe.

Sprawling and Sprouting

A Cronenbergian grotesqueness runs through the novel, drips and seeps from every page in a flood of organic appliances and symbiotic biotech. In the first paragraphs and pages alone, there are stringbeasts and coffin eels, bloodtide wayfarers, skinboard-panelled walls, fabric knitted with muscle fiber, corpuscytes, synthorganic digestive tracks, winedregs, meatpleats, slimecakes and skingloves, stillveins cords, guidejuices, neurofungi, and so much more.

Sensory Overload and Wear and Tear

The richness of ideas and the sheer magnitude of Torishima’s imagination overwhelm the reader at the beginning of the novel, and the first half relies on the reader’s curiosity to propel it forward.

This creates some problems, however. The lengthy description of settings, creatures, and machines creates a sense of wear and tear and sometimes, paradoxically, achieves the opposite of the intended effect. The bizarre details do not enhance the strangeness but make it more ordinary—and slightly exhausting. The chilling alienation that for example Thomas Ligotti achieves with a few carefully chosen words does not work here to the same degree.

In many places, the novel might have benefited from less description: the president in the first story, for example, is reminiscent of Ligotti’s “Our Temporary Supervisor” or “The Town Manager”, but as he is visualized in so much (admittedly strange) detail, little mystery remains. But still—sentences like “He showed the worker their still-beating hearts—about the size of sesame seeds—as they floated clear of the puffy clouds of red now spreading out in his fingers.” or “The President did perceive sounds by way of a different sort of system, but it tended to interpret the worker’s voice as static.” are simply brilliant.

Sometimes, there is an overload of neologisms and alien concepts that makes sentences completely incomprehensible without context: “He could see the groundship’s coaxer holding an emerald-hued magatama that it had extracted from the corpse of a canvasser.” Elsewhere, some denominations are irritating and (unintentionally?) funny, for example the marrowpens with marrowink, landsoup, cobbleshell roads, exoshelletons or bonemeal bread, and in parts even downright silly (the bonedriver loosens the screwbones).

In the Organic Office

It is remarkable that the novel in all its strangeness manages in wide parts to feel surprisingly familiar in its problems and work experiences, especially in the first quarter. Some of it is mundane to the point of disappointment: annoyed bosses and lack of sleep, long hours that run together in memory; strict hierarchies, mechanical workflows and overbearing superiors that seem to live in a different world; an office that is too cold, compulsion to work despite sickness, bland canteen food, and unloved co-workers. Maybe it is telling that this novel was born from Japanese culture: the complete devotion to the company (“should the product not be ready on time, he would be the one literally cutting his own stomach open”) remind the reader of the clichés of Japanese company loyalty and of Karōshi, death through overwork.

Conclusion

The plot is expertly assembled and unveils the world’s mechanisms from different perspectives. The backstory and origins of the universe are explained only step by step, which is inevitably a bit demystifying, but also creates a lot of epiphanies. The different elements are not arbitrarily scattered throughout the novel, they fit together into a bigger picture: and Torishima uses a world of language and ideas that I find fresh and unused, at least in the context of the still predominately Western Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Despite certain lengths and demanding language a clear recommendation to buy: there is nothing like it.

Experimental Fiction, Literature Review

Publication Date: